Nephrectomy, derived from the Greek words “nephros” (kidney) and “ectomy” (removal), is a surgical procedure involving the partial or complete excision of a kidney. This operation has been a cornerstone of urological and oncological surgery since the late 19th century, when it was first performed successfully by German surgeon Gustav Simon in 1869 for a case of renal tuberculosis. Today, nephrectomy is one of the most common kidney surgeries worldwide, performed for a variety of medical reasons ranging from cancer treatment to organ donation. With advancements in minimally invasive techniques, the procedure has become safer and more efficient, allowing patients to recover faster while preserving as much healthy kidney tissue as possible.

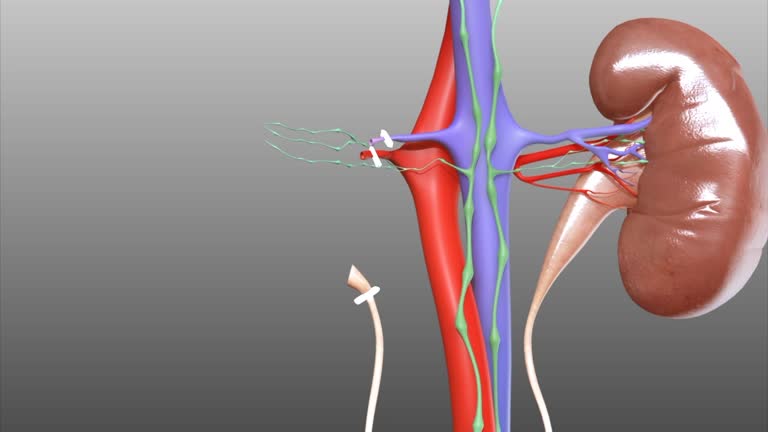

The human body typically has two kidneys, bean-shaped organs located in the retroperitoneal space on either side of the spine. They filter waste from the blood, regulate fluid balance, and produce hormones essential for blood pressure and red blood cell production. Remarkably, a single healthy kidney can sustain normal bodily functions, which is why nephrectomy is feasible without immediate life-threatening consequences for most patients. However, the decision to remove part or all of a kidney is never taken lightly, as it carries risks and long-term implications for renal health.

Nephrectomies are classified based on the extent of tissue removal and the surgical approach. The primary types include:

Radical Nephrectomy: This is the most extensive form, involving the complete removal of the kidney along with surrounding structures such as the adrenal gland, Gerota’s fascia (a fatty envelope around the kidney), and regional lymph nodes. It is primarily indicated for renal cell carcinoma (RCC), the most common type of kidney cancer, especially when the tumor has invaded nearby tissues. In some cases, a portion of the inferior vena cava may also be resected if the tumor extends into it.

Partial Nephrectomy (Nephron-Sparing Surgery): Here, only the diseased portion of the kidney is removed, preserving the rest of the organ. This approach is preferred for small tumors (typically less than 4 cm) or localized conditions like benign cysts or stones, aiming to maintain optimal kidney function. It’s particularly beneficial for patients with pre-existing kidney disease, solitary kidneys, or those at risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Simple Nephrectomy: This involves the removal of the entire kidney without excising adjacent structures like the adrenal gland or lymph nodes. It’s used for non-cancerous conditions such as severe chronic infections (e.g., pyelonephritis), hydronephrosis (kidney swelling due to urine backup), or end-stage kidney damage from conditions like polycystic kidney disease.

Donor Nephrectomy: Performed on healthy individuals to donate a kidney to a recipient with end-stage renal disease. Usually, the left kidney is preferred due to its longer renal vein, which simplifies transplantation. Living donor nephrectomies have revolutionized organ transplantation, with over 6,000 such procedures annually in the United States alone, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN).

Surgical approaches have evolved from traditional open surgery to minimally invasive methods. Open nephrectomy requires a large incision (10-20 cm) on the flank or abdomen, providing direct access but leading to longer recovery times. Laparoscopic nephrectomy, introduced in the 1990s, uses small incisions and a camera-guided scope, reducing blood loss and hospital stays to 2-4 days. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, utilizing systems like the da Vinci Surgical System, offers enhanced precision through 3D visualization and articulated instruments, further minimizing complications.

The decision for nephrectomy is guided by diagnostic tools like ultrasound, CT scans, MRI, and biopsy. Common indications include:

Malignancy: Renal cell carcinoma accounts for about 90% of kidney cancers, with over 76,000 new cases diagnosed annually in the U.S. (American Cancer Society data). Nephrectomy is curative for localized tumors but may be palliative for advanced stages.

Infections and Obstructions: Recurrent urinary tract infections, kidney stones causing irreversible damage, or congenital anomalies like duplicated ureters may necessitate removal to prevent sepsis or hypertension.

Trauma: Severe kidney injury from accidents, such as blunt abdominal trauma or penetrating wounds, can lead to emergency nephrectomy if bleeding cannot be controlled.

Donation: Living donors undergo rigorous screening to ensure they have no underlying conditions like hypertension or diabetes, which could impair their remaining kidney.

Other Conditions: Rare indications include renovascular hypertension (uncontrolled high blood pressure from renal artery stenosis) or xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, a destructive inflammatory process.

For partial nephrectomies, guidelines from organizations like the American Urological Association (AUA) recommend it as the standard for T1a tumors (small, confined to the kidney) to preserve glomerular filtration rate (GFR), a key measure of kidney function.

Preparation for nephrectomy involves a multidisciplinary team including urologists, anesthesiologists, and nephrologists. Patients undergo blood tests, imaging, and cardiac evaluation. Fasting is required preoperatively, and prophylactic antibiotics are administered to prevent infection.

Under general anesthesia, the patient is positioned laterally. In open surgery, an incision exposes the kidney, which is mobilized by ligating (tying off) its blood vessels and ureter. The organ is then removed, and the incision closed with drains to manage fluid buildup.

In laparoscopic or robotic procedures, trocars (small ports) are inserted into the abdomen, insufflated with carbon dioxide for visibility. The surgeon dissects the kidney using specialized instruments, clamps vessels to minimize warm ischemia time (the period the kidney is without blood flow, ideally under 20-30 minutes for partial nephrectomies), and extracts the specimen in a retrieval bag through an enlarged port. Hemostasis is ensured with sutures or sealants before closure.

The procedure duration varies: 2-4 hours for simple cases, up to 6 hours for complex radical ones. Blood transfusion may be needed in 5-10% of cases.

While nephrectomy is generally safe with a mortality rate under 1%, potential risks include:

Intraoperative: Bleeding (from the renal artery/vein), injury to adjacent organs (bowel, spleen, liver), or conversion from laparoscopic to open surgery (occurs in 2-5% of cases).

Postoperative: Infection (wound or urinary), blood clots (deep vein thrombosis), pneumonia, or ileus (bowel paralysis). Long-term, there’s a 20-30% risk of CKD progression, hypertension, or proteinuria.

Donor nephrectomies have even lower complication rates (under 5%), but donors face a slight increased risk of gestational hypertension in women or end-stage renal disease later in life (about 0.5% lifetime risk, per studies in the New England Journal of Medicine).

Pain management involves opioids initially, transitioning to non-steroidal anti-inflammatories. Monitoring for urine output and GFR is crucial.

Hospital stays range from 1-3 days for minimally invasive procedures to 5-7 days for open surgery. Patients are encouraged to mobilize early to prevent clots, with a clear liquid diet advancing as tolerated. Drains and catheters are removed within 24-48 hours.

At home, recovery takes 2-6 weeks. Restrictions include avoiding heavy lifting (>10 lbs) for 4-6 weeks and driving until off narcotics. Follow-up includes wound checks, blood work for creatinine levels, and imaging to assess the remaining kidney.

Lifestyle adjustments are key: A low-sodium diet, hydration (2-3 liters daily), blood pressure control, and avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs (e.g., excessive NSAIDs) help protect renal function. Regular exercise and smoking cessation further mitigate risks.

For donors, psychological support addresses any donor remorse, though satisfaction rates exceed 95%.

Most patients lead normal lives post-nephrectomy, with the contralateral kidney compensating via hypertrophy (growth) within weeks, restoring 70-80% of original function. Athletes and pilots have successfully undergone the procedure. However, vigilance is needed: Annual check-ups monitor for proteinuria or declining GFR, and patients should inform healthcare providers of their status before new medications or surgeries.

In children, partial nephrectomy is prioritized to support growth, as unilateral kidney absence can affect development if not managed.

Innovations like single-port laparoscopy and fluorescence-guided surgery (using indocyanine green dye) are enhancing precision. Alternatives to full nephrectomy include ablation therapies (radiofrequency or cryoablation) for small tumors, active surveillance for low-risk cases, or targeted therapies like tyrosine kinase inhibitors for metastatic RCC.

nephrectomy stands as a testament to the remarkable progress in surgical innovation and patient-centered care within urology and nephrology. From its historical roots as a life-saving measure for infectious diseases to its modern role in combating renal cell carcinoma and facilitating life-giving organ donations, this procedure has evolved dramatically. The shift toward nephron-sparing techniques, such as partial nephrectomy and robotic-assisted laparoscopy, underscores a commitment to preserving renal function while achieving oncologic efficacy. These advancements have not only reduced perioperative risks—lowering complication rates to under 5% in many cases—but also shortened recovery times, enabling patients to resume normal activities with minimal disruption.

Yet, nephrectomy is not without its challenges. The potential for chronic kidney disease progression, hypertension, and the psychological impact on donors highlight the need for meticulous preoperative evaluation, intraoperative precision, and lifelong postoperative monitoring. Multidisciplinary approaches, incorporating nephrologists, oncologists, and transplant specialists, are essential to optimize outcomes and mitigate long-term sequelae. Emerging technologies, including ablation alternatives and molecular-targeted therapies, promise to further refine treatment paradigms, potentially reducing the necessity for invasive surgery in select cases.

Ultimately, nephrectomy exemplifies the delicate balance between curative intent and quality-of-life preservation. For patients facing kidney pathology, it offers a pathway to survival and normalcy, supported by a single, adaptive remaining kidney. As research continues to unravel the complexities of renal physiology and tumor biology, the procedure’s role will likely expand, ensuring that nephrectomy remains a cornerstone of renal medicine for generations to come. Patients and donors alike are empowered by education and support, fostering resilience in the face of surgical intervention.

Chat With Me