A Dialysis Catheter is a specialized medical device used to provide access to the bloodstream for dialysis treatment. Dialysis is a life-saving therapy for patients with severe kidney failure, where the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste and excess fluids from the body. The catheter allows blood to be drawn out, filtered by a dialysis machine, and returned to the body.

Dialysis catheters are especially important for patients who need immediate dialysis and do not yet have a permanent access, such as an arteriovenous (AV) fistula or graft. They may also be used in patients for whom other access options are not possible. Understanding dialysis catheters helps patients and caregivers appreciate their role, maintenance needs, and potential risks.

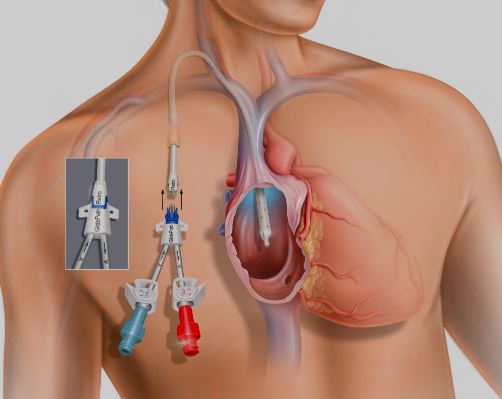

The catheter is a long, flexible tube inserted into a large central vein, most commonly the:

Internal jugular vein (neck) – preferred site due to lower complication rates.

Femoral vein (groin) – used in emergencies or short-term dialysis.

Subclavian vein (below the collarbone) – less commonly used due to risk of vein narrowing.

Dialysis catheters have two lumens (channels):

Arterial lumen – removes blood from the body to the dialysis machine.

Venous lumen – returns cleansed blood back to the body.

These catheters can be temporary (non-tunneled) for short-term use, or permanent (tunneled) for long-term dialysis access.

A Dialysis Catheter is placed when a patient requires urgent or ongoing dialysis and lacks other suitable vascular access. Common reasons include:

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI): Sudden kidney failure requiring immediate dialysis.

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): Patients awaiting AV fistula or graft maturation.

Failed AV fistula or graft: When permanent access is blocked or unusable.

Contraindications for surgery: Patients too weak or high-risk for fistula/graft surgery.

Bridging access: While waiting for kidney transplantation.

The need for a dialysis catheter arises from symptoms of kidney failure, such as:

Swelling in legs, ankles, or face (fluid overload).

Shortness of breath due to fluid in lungs.

Nausea, vomiting, or loss of appetite.

Severe fatigue and weakness.

Confusion or decreased alertness due to toxin buildup.

High blood pressure that is difficult to control.

After catheter placement, patients may experience:

Mild soreness or bruising at the insertion site.

Swelling or discomfort in the neck or chest.

Infections or clotting if complications develop.

Before placing a dialysis catheter, doctors evaluate kidney function and overall health through:

Blood tests: Elevated creatinine, urea, electrolyte imbalances.

Urinalysis: To assess urine output and kidney performance.

Ultrasound or imaging: To evaluate vein patency and guide safe insertion.

Physical examination: To check for swelling, vascular health, and infection risks.

Dialysis catheters themselves are not a treatment but an access route for dialysis. The treatment options for patients with kidney failure include:

Hemodialysis: Requires catheter or permanent vascular access.

Peritoneal dialysis: Uses a catheter placed in the abdomen instead of veins.

Kidney transplantation: Definitive treatment but not always immediately available.

Non-surgical management involves optimizing medical therapy for kidney disease until access is required.

The placement of a dialysis catheter is a sterile, minor surgical procedure, usually performed under local anesthesia.

Steps involved:

Preparation: The skin is cleaned, and local anesthesia is applied.

Vein access: A needle is inserted into the chosen central vein, guided by ultrasound.

Catheter insertion: A guidewire is threaded through the needle, followed by catheter placement.

Positioning: The catheter is advanced until the tip rests in a large central vein near the heart (superior vena cava).

Securing: The catheter is stitched or secured with a special dressing to prevent dislodgement.

Confirmation: Imaging (X-ray) is done to verify correct placement.

For tunneled catheters, the device is placed under the skin for part of its length, reducing infection risk and allowing longer use.

After catheter placement, careful care is needed to ensure function and reduce risks:

Hospital monitoring: Patients are observed for bleeding or complications immediately after placement.

Catheter care: Dressing changes, cleaning, and flushing to prevent infection and clotting.

Activity restrictions: Avoid heavy lifting or pulling on the catheter site.

Follow-up: Regular evaluation by dialysis staff and nephrologist.

Transition planning: Efforts should be made to shift to a permanent access (fistula or graft) for long-term dialysis.

Although generally safe, dialysis catheters carry higher complication risks than permanent vascular access. These include:

Infection: At the insertion site or bloodstream infections (sepsis).

Clotting or blockage: Reduces effectiveness of dialysis.

Bleeding: During or after insertion.

Vein damage or narrowing: Especially with subclavian placement.

Catheter malfunction: Poor flow or dislodgement.

Air embolism: Rare but potentially serious complication if air enters bloodstream.

Dialysis catheters are effective for providing immediate access to dialysis, but they are not ideal for long-term use due to higher complication rates. With proper care, a tunneled catheter can last for months to years. Transitioning to a permanent AV fistula or graft remains the best long-term solution. Patient outcomes depend on timely dialysis, good catheter care, and management of underlying kidney disease.

Patients with a dialysis catheter should seek medical care urgently if they experience:

Fever, chills, or signs of infection at the catheter site.

Redness, swelling, or pus around the insertion site.

Sudden chest pain or difficulty breathing.

Catheter dislodgement or leakage.

Poor dialysis performance (machine alarms, low blood flow).

Unexplained bleeding.

A Dialysis Catheter provides essential access for life-saving hemodialysis in patients with kidney failure. While invaluable in emergencies and as a bridge to permanent vascular access, catheters carry higher risks of infection and other complications. Proper placement, care, and follow-up are crucial for safe and effective use. Patients should work closely with their healthcare team to transition to more permanent access, such as an AV fistula or graft, whenever possible.

If you or a loved one requires dialysis, consult with your nephrologist to understand the best access option for long-term kidney care and quality of life.

Chat With Me