A kidney transplant is a surgical procedure that replaces a diseased or failing kidney with a healthy one from a donor. The kidneys are vital organs responsible for filtering waste products from the blood, regulating fluid balance, and maintaining electrolyte levels. When kidneys fail, a condition known as end-stage renal disease (ESRD), patients often rely on dialysis—a machine that performs some kidney functions—to survive. However, dialysis is not a cure and can be exhausting and costly. A kidney transplant offers a more natural and effective long-term solution, significantly improving quality of life and extending lifespan.

Kidney transplants have revolutionized treatment for kidney failure since the first successful procedure in 1954. Today, thousands of transplants are performed annually worldwide, thanks to advancements in immunosuppressive drugs, surgical techniques, and organ preservation methods. For many patients, it’s not just a medical intervention but a second chance at a normal life—free from the rigors of dialysis and its side effects like fatigue, anemia, and dietary restrictions.

Kidney failure can result from various causes, including diabetes, high blood pressure, chronic glomerulonephritis, polycystic kidney disease, or lupus. These conditions damage the kidneys over time, leading to ESRD when kidney function drops below 10-15% of normal capacity. Symptoms at this stage include swelling (edema), extreme fatigue, nausea, and high blood pressure that doesn’t respond to medication.

Not everyone with kidney disease qualifies for a transplant immediately. Candidates undergo thorough evaluations to assess overall health, including heart function, lung capacity, and psychological readiness. Age is not a strict barrier—transplants have been successfully performed on children as young as one year and adults over 70. However, factors like active infections, cancer, or severe heart disease may disqualify patients. For those eligible, transplantation is often preferred over long-term dialysis because it restores near-normal kidney function, allowing patients to eat a varied diet, travel more freely, and engage in physical activities.

There are two primary types of kidney transplants: living donor and deceased donor.

Living Donor Transplants: These involve a healthy donor—often a family member, friend, or even a stranger—who voluntarily donates one of their kidneys. Living donors can be related (like siblings or parents) or unrelated, and the procedure is laparoscopic, meaning smaller incisions and faster recovery for the donor (typically 2-6 weeks). The advantage is that the kidney functions immediately upon transplantation, and recipients often experience better long-term outcomes. Paired exchange programs allow incompatible donor-recipient pairs to swap kidneys with another pair, expanding options.

Deceased Donor Transplants: Kidneys from individuals who have passed away and consented to organ donation (or whose families consent) are used. These are allocated through national registries like the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) in the US, based on factors such as blood type, tissue match, wait time, and medical urgency. Wait times can range from months to years, averaging 3-5 years in many countries. Deceased donor kidneys may require a short period of delayed function post-transplant, but they save countless lives.

In both cases, the transplanted kidney is placed in the lower abdomen, near the groin, while the recipient’s original kidneys (if non-cancerous) are usually left in place unless they cause issues.

The journey to a kidney transplant begins with referral to a transplant center. The evaluation process, which can take several months, includes blood tests, imaging (like ultrasounds or CT scans), and consultations with nephrologists, surgeons, surgeons, psychologists, and social workers. Potential recipients must demonstrate commitment to post-transplant care, including medication adherence and lifestyle changes.

Once listed on a transplant waitlist (for deceased donors), patients carry a pager or use apps to stay alert for a match. For living donors, compatibility testing is crucial—blood type, HLA (human leukocyte antigen) typing, and cross-matching ensure the recipient’s immune system won’t attack the kidney.

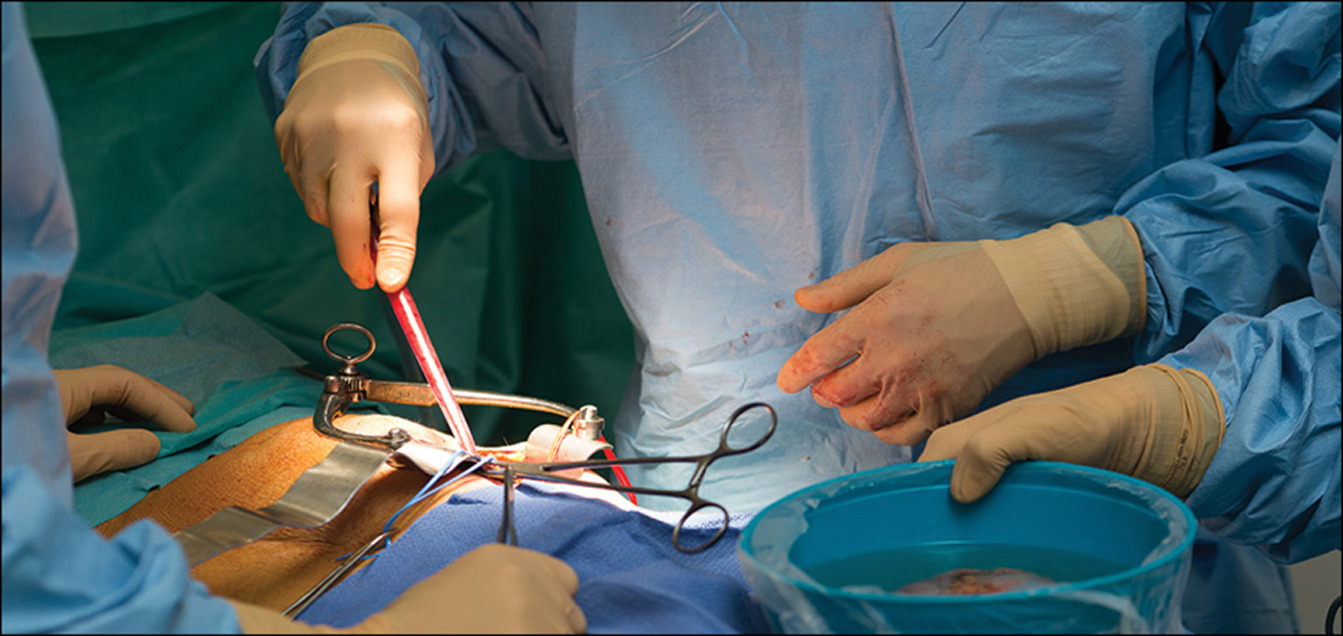

On transplant day, both donor and recipient undergo surgery under general anesthesia. The procedure lasts 3-4 hours. Surgeons remove the donor kidney (nephrectomy) and connect the new kidney’s blood vessels and ureter to the recipient’s bladder and iliac artery/vein. The old kidneys are rarely removed unless infected or causing pain.

Post-surgery, patients spend 5-10 days in the hospital. The new kidney typically starts producing urine within hours or days, a promising sign called “immediate graft function.”

Successful transplants hinge on compatibility to minimize rejection. Key factors include:

Blood Type: ABO compatibility is essential; type O donors are universal, while type AB recipients are universal acceptors.

HLA Matching: HLA antigens on cells must match as closely as possible (out of six markers). A perfect match reduces rejection risk, especially in unrelated donors.

Cross-Match Test: This detects pre-formed antibodies in the recipient’s blood that could attack the donor kidney. A negative cross-match is ideal.

PRA (Panel Reactive Antibody): Measures sensitization levels from prior transfusions, pregnancies, or transplants. Highly sensitized patients face longer waits.

Advances like desensitization protocols—using plasmapheresis or IVIG—allow transplantation for previously incompatible pairs, broadening access.

While kidney transplants are safe, with a success rate over 95% in the first year, risks exist. Surgical complications include bleeding, infection, or blood clots (affecting 5-10% of cases). The biggest long-term threat is rejection, where the immune system attacks the foreign kidney. Acute rejection occurs in 10-15% within the first year and is treated with steroids or biologics. Chronic rejection, a gradual process, can lead to graft failure after 10-15 years.

Immunosuppressive drugs like tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone prevent rejection but increase risks of infections, diabetes, high cholesterol, and skin cancer. Patients must balance these side effects with vigilant monitoring—regular blood tests, biopsies if needed, and annual check-ups.

Donor risks are low: living donors have a 0.03% mortality rate and resume normal life quickly, with their remaining kidney compensating fully.

Recovery is a phased process. In the hospital, pain management, IV fluids, and monitoring for urine output are priorities. Once home, patients follow a regimen of 8-12 medications daily, avoid crowds to prevent infections, and adhere to a low-salt, heart-healthy diet. Light exercise, like walking, starts within weeks, building to full activity in 3-6 months. Most return to work or school within 2-3 months.

Long-term, a transplanted kidney can last 15-20 years (longer for living donor grafts). Success depends on compliance: missing doses or ignoring symptoms like fever or swelling can spell trouble. Support groups and transplant coordinators provide emotional and practical guidance. Many recipients enjoy hobbies, travel, and family life unhindered, though alcohol and smoking are discouraged.

Kidney transplant success rates are impressive: 98% one-year survival for living donor kidneys and 96% for deceased, per UNOS data. Five-year graft survival exceeds 85%. Factors like donor age, recipient health, and timely care influence outcomes. In children, transplants yield even better results, often lasting decades.

The field is evolving. Xenotransplantation—using genetically modified pig kidneys—shows promise in trials, potentially ending waitlists. 3D bioprinting and stem cell-derived organs are on the horizon. Increasing living donation through education and incentives remains key to addressing the global shortage: over 100,000 waitlisted in the US alone, with 17 dying daily.

A kidney transplant isn’t just surgery—it’s a bridge to renewed vitality for those battling ESRD. While challenges like wait times and lifelong medications persist, the benefits far outweigh them for most. If you or a loved one faces kidney failure, consult a specialist early. Raising awareness about organ donation can save lives—consider registering as a donor today. With ongoing innovations, the future of kidney transplantation is brighter than ever, offering hope to millions worldwide.

Chat With Me