Renal artery stenting is a minimally invasive medical procedure designed to treat renal artery stenosis, a condition characterized by the narrowing of one or both arteries that supply blood to the kidneys. This narrowing can lead to reduced blood flow, which may cause hypertension (high blood pressure) and impaired kidney function. The goal of renal artery stenting is to restore adequate blood flow to the kidneys, thereby improving kidney function and controlling blood pressure.

Renal artery stenosis is most commonly caused by atherosclerosis, a condition where fatty deposits build up on the artery walls, leading to narrowing and hardening of the arteries. Less commonly, fibromuscular dysplasia, a condition involving abnormal cell growth in the artery walls, can cause stenosis. When the renal arteries are narrowed, the kidneys receive less oxygen-rich blood, which can trigger the release of hormones that raise blood pressure. This can result in renovascular hypertension, a form of secondary hypertension that is often difficult to control with medication alone.

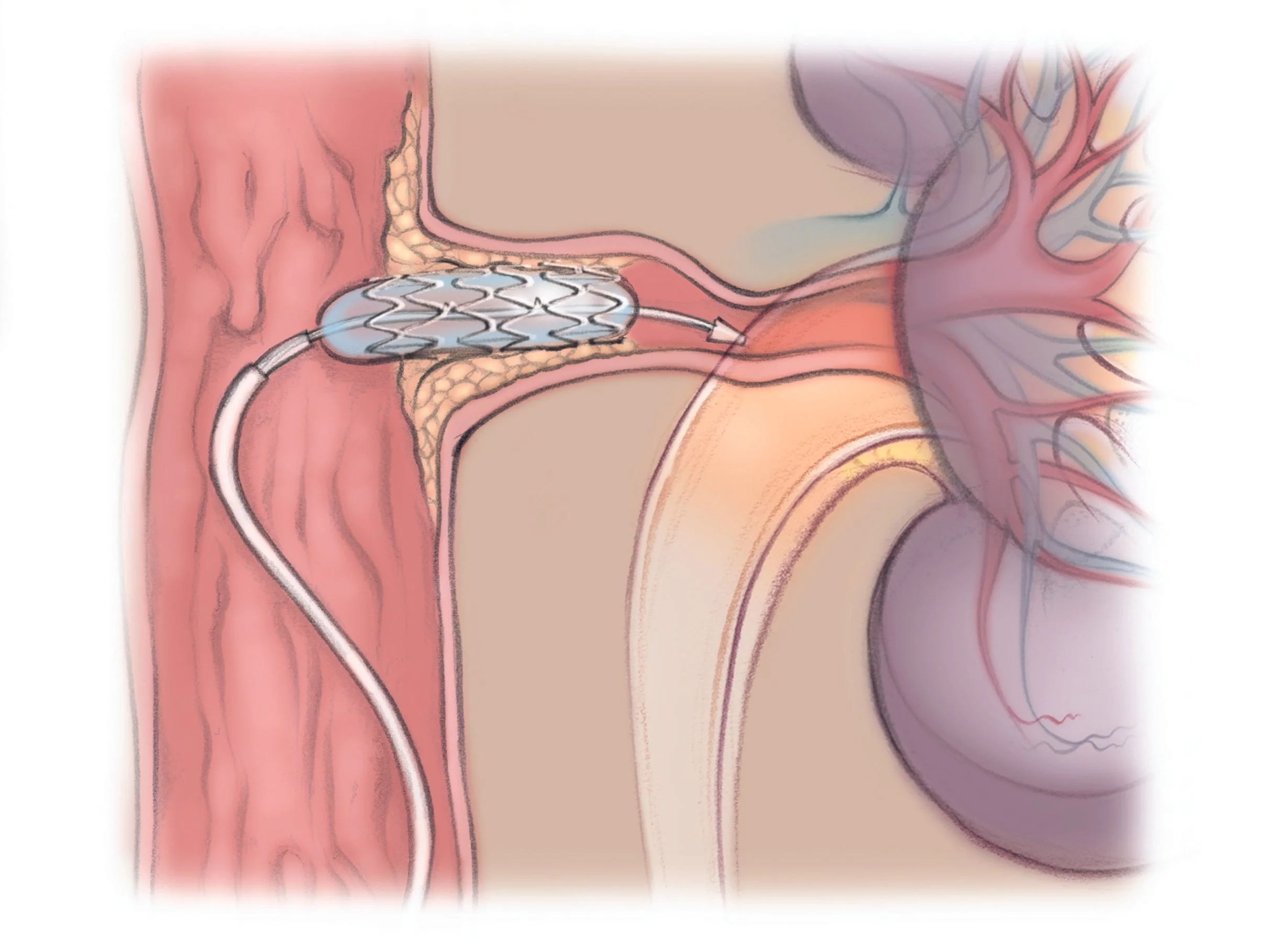

Renal artery stenting involves the placement of a small, metal mesh tube called a stent inside the narrowed renal artery. The stent acts as a scaffold to hold the artery open, preventing it from collapsing or becoming blocked again. This procedure is typically performed using a catheter-based technique known as percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty (PTRA). During the procedure, a balloon catheter is threaded through the blood vessels to the site of the narrowing. The balloon is inflated to widen the artery, and then the stent is deployed to keep the artery open.

Renal artery stenting is generally recommended for patients who have significant renal artery stenosis accompanied by symptoms such as:

Not all patients with renal artery stenosis require stenting. The decision to proceed with the procedure depends on the severity of the stenosis, the patient’s symptoms, and the overall health of the kidneys.

Renal artery stenting is performed in a catheterization laboratory under local anesthesia, often with mild sedation. The interventional radiologist or vascular specialist inserts a catheter, usually through the femoral artery in the groin, and guides it to the renal artery using real-time X-ray imaging (fluoroscopy). Once the catheter reaches the narrowed segment, a balloon is inflated to dilate the artery, and the stent is placed to maintain vessel patency.

The stent is typically made of a metal alloy such as stainless steel or nitinol, which is biocompatible and designed to resist corrosion. Some stents are coated with medication to reduce the risk of restenosis (re-narrowing of the artery).

The primary benefit of renal artery stenting is the restoration of blood flow to the kidneys, which can lead to:

Studies have shown that stenting can achieve technical success rates exceeding 98%, meaning the artery is successfully opened in the vast majority of cases.

While renal artery stenting is generally safe, it carries some risks, including:

To minimize embolic complications, embolic protection devices such as the GuardWire may be used during the procedure. These devices capture debris that might otherwise travel downstream and cause blockages.

After renal artery stenting, patients are typically monitored for several hours to ensure there are no immediate complications. They may be prescribed antiplatelet medications like aspirin or clopidogrel to prevent blood clots from forming around the stent. Blood pressure and kidney function are closely followed through regular check-ups and imaging studies such as Doppler ultrasound or CT angiography.

Long-term follow-up is important to detect restenosis early and to manage any ongoing hypertension or kidney issues. Lifestyle modifications, including a healthy diet, exercise, and smoking cessation, are also recommended to reduce the progression of atherosclerosis.

Despite the technical success of renal artery stenting, its impact on long-term clinical outcomes such as survival, kidney function preservation, and blood pressure control has been debated. Some clinical trials have suggested that medical therapy alone may be as effective as stenting in certain patient populations, especially those with stable kidney function and controlled hypertension.

However, for patients with severe stenosis and refractory symptoms, stenting remains a valuable option. Advances in stent technology, imaging techniques, and embolic protection have improved the safety and efficacy of the procedure.

Research explores genetic factors in RAS progression and AI-assisted imaging for precise stenosis grading. Drug-eluting stents with antiproliferative agents aim to cut restenosis below 5%. Personalized medicine, integrating genomics and hemodynamics, promises tailored interventions.

In summary, while controversies persist, renal artery stenting remains a cornerstone for symptomatic RAS, balancing risks with potential for life-enhancing improvements in hypertension and renal health. Patient-centered decisions, guided by multidisciplinary teams, optimize results.

Renal artery stenting is a well-established, minimally invasive treatment for renal artery stenosis that helps restore blood flow to the kidneys, improve blood pressure control, and preserve kidney function. It involves placing a metal stent within the narrowed artery to keep it open. While generally safe and effective, the procedure requires careful patient selection and follow-up to optimize outcomes. Ongoing research continues to refine the indications and techniques to maximize the benefits of this important vascular intervention.

Chat With Me